Staff teams in a range of settings have used Cognitive Analytic Therapy as a framework to change how they respond to behaviour that challenges.

This includes services for people with intellectual or learning disabilities. In these settings CAT has been used help reduce the use of restraint, seclusion, and other force. Another term for this is restrictive practice.

Restrictive practice can take place more often in services where staff teams feel overwhelmed by behaviour which they experience as challenging. It takes place in a range of settings, for example in inpatient psychiatric services. Some groups of people are more likely than others to be in receipt of restrictive practice.

“For an individual’s behaviour to be viewed as challenging, a judgement is made that this behaviour is dangerous, frightening, distressing or annoying and these feelings, invoked in others, are in some way intolerable or overwhelming.”

Learning Disabilities Professional Senate 2016, page 8, quoted in Varela 2019

Staff may resort to the use of physical restraint, or use drugs to sedate the person. On some occasions, they may separate the person and keep them in seclusion, apart from other people. They may have belongings removed to reduce the chance of harm to themselves, to others or to things around them.

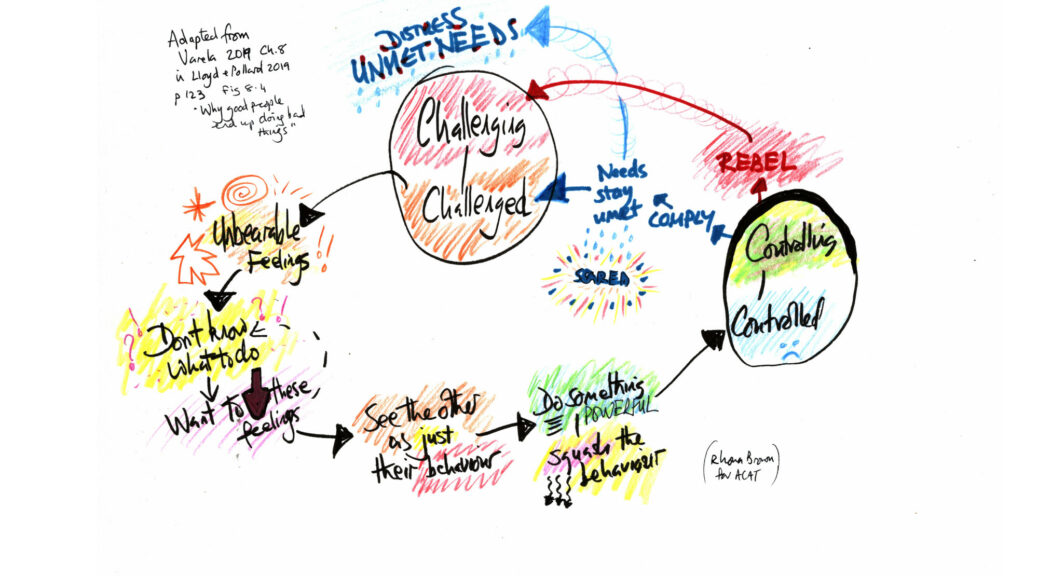

To the person this may feel as though past experiences of neglect and abuse are being repeated. As a result, they may feel threatened, distressed and more wary of staff. Staff may also feel wary or scared, expecting a repeating pattern of challenge and violence. As a result they become primed to “contain behaviour” rather than respond to distress. This pattern can carry on repeating in a care setting because a cycle has been set up.

Staff can use a CAT-informed approach, supported by an accredited CAT therapist in reflective practice meetings. It may then be easier to step back, check their own emotional reactions and think about their responses. Relationship roles that invite them to act in forceful and controlling ways may become much more clear. This provides space to step out of that role and come up with other ways to respond to the person’s feelings and behaviour. Often this is about tuning in to the person’s feelings, even if the person doesn’t have language to express themselves.

Staff can start to learn how to spot patterns of behaviour that they recognise as signalling distress rather than challenge. They can tune in to problem cycles at an early stage. This can help them to explore alternatives, and build up more confidence and skills for responding to the person in ways other than restraint.

The model has been used in a workshop offered by accredited CAT therapists Jo Varela and Phil Clayton through the Restraint Reduction Network. You can read more about this in their blog at this link.

It is also one of the approaches which informs the work of another accredited CAT therapist, Lianne Franks. She is lead for Mersey Care NHS Foundation Trust’s “No Force First” (NFF) initiative within its Learning Disability Services. The Trust’s NFF initiative has been recognised internationally and in 2018 received an award from the Restraint Reduction Network for Innovative Practice.

You can read more about CAT in learning disability settings in the book Cognitive Analytic Therapy for People With Intellectual Disabilities and their Carers.

There are also two chapters on this subject in the book Cognitive Analytic Therapy and the Politics of Mental Health

Thanks are extended to Jo Varela and Lianne Franks for helpful contributions to this page.

CAT in Teams: Reducing Restraint by ACAT Public Engagement Team

CC BY-SA 4.0